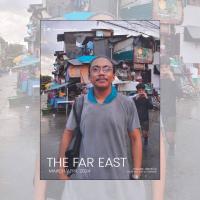

Lanieta with the hearing impaired students among whom she works in the Philippines. Photo: Lanieta Tamatawale

In our world today, we study the signs of the times: climate change, migration and the COVID-19 pandemic, just to name a few. We look for signs to reassure us that we are heading in the right direction, that our loved ones are safe and that we are secure. Although we live in the midst of evil and sin, we continue to seek out these signs.

It is many years now since I have lived in my homeland of Fiji, but each October 10, as the land in which I was born and grew up celebrates its independence, my thoughts travel back across the seas to the culture within which I first formed my identity.

Fiji is an island nation in the Pacific Ocean and with its tropical climate and rich soil became an attractive prize for European settlers seeking to grow sugar and other crops of value on the international market. It took time for the local people to understand the full consequence of the guile of the settlers in manipulating the traditional barter system on which the age-old economy was based, and the interlopers managed to accumulate significant swathes of land at the cost of an axe or bottle of whisky.

In May 1865, the chiefs of Fiji established a Confederacy of Independent Kingdoms of Viti, but within a couple of years it split into two warring kingdoms, with one chief, Seru Cakobau, unilaterally declaring himself above other chiefs. This was quite astonishing, because chiefs only hold respect in their own province, or vanua, and if anyone crossed boundaries, it meant war.

And war it was, but Cakobau triumphed and in 1871, with the support of the foreign settlers, declared himself king and established a united Fijian kingdom. However, it was to be short lived. In 1874, the United States government, which had supported Cakobau strongly, turned on its old ally and accused the king of destroying the home and property of its consul. It declared a debt of US$44,000, to be paid in cash. Spuriously, the supposed crime dated back 15 years.

As king reigning over a produce barter economy, Cakobau was unable to pay the debt and fearing an all-out attack from the United States, he, along with the other chiefs, agreed to cede Fiji to Great Britain in 1874.

Fiji was to remain a colony of Great Britain until 10.00am on 10 October 1970, when it signed another deed with the colonial master, only this time not with a heavy heart, but with jubilation and a celebratory air of a newly established Republic of Fiji.

It was a radically different Fiji from the one ceded to the British almost a century earlier. Gone was the cannibalism of times past, replaced by sophisticated political structures with a Fijian chief as the first prime minister. Education had become universal and Christianity a strong influence on the culture.

Lanieta with Columban lay missionaries in the Philippines. Photo: Lanieta Tamatawale

These were firm signs of hope of a better future. However, Fiji may have freed itself from the shackles of colonial rule, but a strong trace of the blood of the settlers from Europe, the United States and Asia still lingered in the population, bequeathing tensions that were to manifest themselves in four coups d’état in the space of 20 years.

In 1987, the elected government was overthrown in a coup led by a military commander, Sitiveni Rabuka. Then again, in the same year, the governor general, Ratu Penaia Ganilau, was deposed. In 2000, another military commander, George Speight, led a rebellion against a multicultural government and in 2006, yet another military officer, Frank Bainimarama, deposed the government, before becoming the country’s long serving prime minister.

Many lives were lost in these coups d’état. There was significant migration to Australia, New Zealand and the United States. However, those who remained have continued to go about their normal lives and despite hardships are still smiling, relaxing around the kava bowl and enjoying each other’s company with food, song and dance.

Now another scourge has hit the country, COVID-19, but Fijians are a people of faith and recognise the Church as holding a real sign of Christ in the Eucharist, a sign of what is, what will be, and what is to come. However, signs are not an end in themselves, but only point to another reality, a bigger reality than ourselves, and we, as Christians, are called to point others to Christ.

The Fijian government is facing an election later this year and campaigning is already in full swing. It knows many people will not be voting for it, as they have seen how it mishandled the Delta variant of the pandemic that has hit the country and many are not happy with its preponderance to lie. People are seeing the signs and praying for an honest and fair election.

Lanieta, (second row, fourth from the left) with her classmates at the New Life course for formators, Sydney. Photo: Lanieta Tamatawale

We pray we will allow Jesus to use us as a real sign of the truth and faith, that by our very lives we may proclaim the sentiment of the psalm, “The Lord has made his salvation known”. Yes, through us. You and me. Our presence is a sign of God’s love.

Columban lay missionary, Lanieta Tamatawale, from Fiji, lives and works in the Philippines.

Listen to "My homeland across the sea"

Related links

- Read more from The Far East - March/April 2022