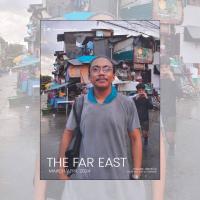

Rochelle Mordeno - Photo: Rochelle Mordeno

Rochelle Mordeno - Photo: Rochelle Mordeno

The municipality of Opol in the province of Misamis Oriental overlooks the picturesque Macajalar Bay on the north-west coast of Mindanao, the southern-most island of the Philippines, but its scenic outlook betrays the poverty and desperation of the people who live there.

However, the proximity of the province to the provincial capital of Cagayan de Oro has proved a lifeline to those of this struggling rural population with the resolve and determination to improve their lot in life.

The steady trickle of migrants into the city may have added to its urban sprawl, but the enterprising nature of the new comers has contributed much energy and creativity to its life. The women have scoured the streets for any opportunity they can find to earn a living. Able-bodied men have boosted construction gangs, driven taxis and lugged freight to complement the meagre earnings of their families. With courage and determination, they have slowly built new settlements on rented land and persisted in improving their homes despite the absence of secure tenure.

However, the level of support received from local authorities has in no way matched the optimism and verve demonstrated by these energetic migrants from rural areas. Bureaucracy and political patronage manifested themselves in the lack of provision of necessary infrastructure, resulting in limited electricity and water supplies, obstructed access to markets, education and other essential services. This has severely affected not only the work these industrious migrants have been able to access, but also contributed to a worrying level of poverty and illiteracy.

Divine Mercy Village is a case in point. Many of its residents are survivors of Typhoon Sendong, which ravaged the area in 2013. They did their best to meet the needs of their families, and with support from parishes in the archdiocese of Cagayan de Oro, religious congregations, civil society organisations, government agencies and international donors got back on their feet and began life anew.

However, another calamity was to beset them, and while not as dramatic as the typhoon, the disquieting emergence of the coronavirus pandemic was equally as daunting. To curb the spread of the virus, the government issued health protocols and instructions: use of facemasks, social or physical distancing, curfews and a ban on liquor.

These restrictions hit those who eke out their living from day to day the hardest, but rather than sitting quietly and feeling anxious about the future and the risk of infection, the residents of Divine Mercy Village, especially the women and young people, began exploring new ways to survive.

Putting Food on the Table

Irene Jimenez, a resident of the Divine Mercy Village, knew what it was like to live in critical times. She had experienced the destructive winds of Typhoon Sendong and understood the threat the pandemic posed to the food supply and the health of her family.

The ever resourceful woman began promoting what was termed square-foot gardening. Tilling the soil in the small space outside her home allowed her to create a four-by-two-foot plot in which she planted vitamin-rich Malabar spinach (alugbati).

Come harvest time, she reaped more than her family needed and picked up 55 pesos ($1.44) from the sale of her alugbati. Not a big amount, but enough to confirm success and inspire her neighbours to join the venture, resulting in various kinds of produce beginning to sprout around the perimeters of the homes clustered in the area.

People got on the bandwagon knowing that eating organically grown food would contribute to the health of their families. They also swatted up on the nature of the coronavirus to dispel feelings of fear and anxiety, helping their community to become more cohesive.

Watching the gardens thrive gave people reason to smile and laugh again, and Irene tucked the proceeds of her first crop into her treasure box as a kind of good luck charm. For her, the vegetable garden represented the hope in her heart that there would always be food on her family table.

I see this as an example of the oft’-quoted maxim, “to see is to believe.” Her neighbour, Joel Tabornal, had been sceptical of Irene’s efforts. He told her she was wasting her time, but his wife, Conception, was impressed.

Conception did not allow the cynicism of her husband to deter her and set about doing what she believed would assure her family a supply of free fresh vegetables. She went big in her venture, planting out a nine-square-foot patch. It flourished and once Joel had seen, he believed. He now tends the garden himself.

Petrolina Arana and her husband live beside an idle piece of land and saw the prospect of generating an income. With the consent of the owner of the land, they tilled and planted, even adding a small fishpond with tilapia, a popular delight in many parts of the world. The income they derive helps the family to live more comfortably and by sharing some of their produce with the owner of the land, the relationship between the squatters and the landowner improved. Indeed, in every crisis there is opportunity.

Rochelle Mordeno is an animator for the Columban Justice, Peace and Integrity of Creation office in Mindanao, the Philippines.

Listen to "In every crisis there is opportunity"

Related links

- Read more from The Far East - August 2022