Photo: Ben Brooksbank (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Galway_Station_-_geograph.org.uk_-_2238702.jpg), Galway Station - geograph.org.uk - 2238702, Black and white, https:/ /creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/legalcode

Photo: Ben Brooksbank (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Galway_Station_-_geograph.org.uk_-_2238702.jpg), Galway Station - geograph.org.uk - 2238702, Black and white, https:/ /creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/legalcode

The odd day away from boarding school was something to look forward to. It helped transcend the monotony in an institution that merged the life of a monastery, a barracks and a prison. Looking forward to an away rugby match was a ray of light that shone through the humdrum and tedium of boarding school life.

While difficult, the daily football practice in all kinds of weather was a welcome diversion from class and the inevitable study hours cooped up in a hall trying to strangle time. The only merit the pointless study held was the development of patience that in later life was useful when waiting for a bus, boat or aircraft.

After an away game, our team had a meal together. Win or lose the unpleasant thought of returning to the school barracks hovered beneath the surface of conversation, but one particular return journey after a holiday at home pushed that emotion above the surface. That day etched itself deeply in my memory.

The cold, damp, dreary end of evening in Galway (Ireland) railway station with its dim, monochrome, damp atmosphere broken only by the screams of seagulls in search of abandoned scraps, did nothing for my enthusiasm for school life. When I asked a uniformed man the time of the next train, he replied as if routine, “Forty five minutes, it has to arrive first!” Saying no more, he continued sweeping imaginary dust.

Gradually, people began poking their heads onto the platform. Old and young carried the bags of the traveller and spoke in conspiratorial tone. Others seemed more at home, seasoned travellers I supposed. Occasionally a couple in their mid-20s with small children minded by grandparents appeared. The platform slowly filled with some like myself, a few soldiers, single men and women, family units and those bidding farewell.

The clank of the train in the distance brought unwanted attention. People looked up the track as the hissing hulk emerged from the hanging mist. Most fell silent as it lumbered into the station. Passengers alighted, some met by excited friends, others scurrying away.

Then a crackly announcement. The train at platform one is the boat train (to England)... boarding in 15 minutes. The destination stirred my interest. I ceased being an uninterested bystander.

My attention caught a man, woman and three young children. They stood apart, a family on their own. They were neatly dressed. The man in cloth cap, brown overcoat and well-polished shoes. His wife held a small suitcase. All five were included in the conversation in Gaelic. When the train arrived, the conversation, like the train, came to a clumsy halt, words now inadequate for what had to be faced. The man took the suitcase from his wife. He was leaving, I surmised, to work across the sea in England.

They stood together in a cluster not knowing how to express the pain of separation in painless words. I felt I had become part of the unit and could almost feel the awkwardness of what they wanted to say, but could not. I was unable to articulate for myself what they could not express to each other. I had a strange feeling of a need to give them appropriate words to ease the pain of separation. I felt incompetent, as I had no words even for myself. Secondary school did not deal in the language of emotion.

The all aboard announcement nudged the family close to each other. Silently, they embraced, father and each child, then man and woman in a short intense enrapture that showed the ache of impending separation. In sombre whisper the woman said, “Dia leat (God be with you)”, and he responded, “Dia libh (God to you)”. He stepped onto the train and disappeared down the carriage. They walked along the platform watching him make his way to a seat. From there, the woman and children stood, waving him out of the station, she wiping tears with a handkerchief, the children the backs of their hands.

I was so captivated the train was moving when I boarded. The scene had taken my attention hostage and alleviated my despondency about returning to school. In some obscure manner, sharing their disunion made my own aloneness porous, and in a confused way widened my horizon.

I had already left home and experienced the loss of the familiar, but the scene at the station helped me personalise what a breach in primary relationships really entailed. It would mean more as I grew older. It is my invisible luggage and easily I relate to those who carry it.

The intimacy of that experience at the railway station makes points of departure and arrival interesting, curious and mysterious. On entering airports, bus stops and train stations, ports and border crossings that embody the sadness of departure and the exhilaration of arrival, I feel energised, curious and engrossed by the whirl of movement and the shopping mall of emotion.

I fit into it all as the scene from Galway station continues to re-enact itself. The separation caused by departure, even in state-of-the-art facilities, is as real and palpable today as it was in Galway so many years ago. Departures leave an empty space in the heart, particularly the migrant heart and the hearts of those left behind. Jamaican poet, Grace Nichols, describes a timeless scene at Jamaica’s Kingston airport.

Through the glass of the departure lounge old canecutter watches it all face a study of diasporic brooding Watches the silver shark waiting on the tarmac.

Watches until the shuddering monster takes off with his one and only grandson–leaving behind a gaping hole in the glittering sea we call sky.

But now outside the airport building where emotions are no longer checked in, the old man surrenders to his gut-instinct, sinking to his knees on the grass.

His cane-shot eyes his voice cracked as he wails what his bones know for certain: ‘Nevaar to meet again Nevaar to meet again’

Columban Fr Bobby Gilmore lives and works in Ireland.

Listen to "The invisible luggage of the migrant heart"

Related links

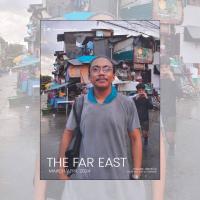

- Read more from The Far East - June 2022