Photo: P199 (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Port_of_Cebu_2. jpg), https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/legalcode

Still the station is a place where you have a soft feeling. It was here that Moses did land when he come to London, and he have no doubt when the time come, if it ever come, it would be here he would say goodbye to the big city. Perhaps he was thinking is time to go back to the tropics, that’s why he feeling sort of lonely and miserable. The Lonely Londoners by Sam Selvon

My first pastoral appointment in the Philippines was to St Michael’s parish in Iligan City in 1964. Apart from the usual shared pastoral responsibilities in the day-to-day running of the parish with two others, there were a hospital, sodalities and other parish organisations needing chaplaincies. One of those assigned to me was chaplain to the port of Iligan. It was a small but busy port serving the needs of the city and the hinterland. Ships and launches arrived from and departed to other ports of the archipelago, transporting people and cargo. Annually, a ship departed from this port to take Muslim pilgrims to Mecca for the Hadj.

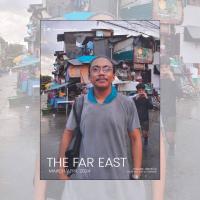

It was a hive of seemingly confused activity: passengers arriving, others departing, dock labourers shouting out to each other, hauling cargo on their shoulders off and on, while others ran up and down the dock with loaded pushcarts followed by anxious owners bartering for the worker’s charge. Taxi drivers called out their fares to various destinations both in the city and the province. Others sold instant snacks, drinks, and cigarettes. Music blared from a variety of shops and bars approaching the dock. A lone, armed policeman surveyed the scene, shushing away stray canines. It brought the movie 'Along the Waterfront' alive.

Adjacent to the port was a residential area comprised mainly of unplanned temporary run-up wooden and bamboo tin-roofed shacks devoid of sanitation, with the open sewers cleaned by the incoming and outgoing tides. Water supply was available in sporadic standpipes. Really, it was a slum area. But it was here the workers and their families lived in the hope of daily paid work on the docks. They depended on the local shipping agent for a day’s work. And the dock would not have functioned without them. The ship’s siren approaching the port was a call to work.

I visited the port area three times a week. It was a relaxing experience watching the arrival of a ship and the accompanying activity. Passengers disembarking, welcomed happily by relatives and friends; passengers leaving, huddled in small groups waiting to embark, then the hugs, tears and sadness of departure, breaking primary relationships, waving handkerchiefs and head coverings. Being there watching departures and arrivals, I had a feeling of being in contact with the world. Watching the workers put the gangplank in place, I also had a feeling that someone, one day, would disembark that I might know.

Then one evening in early October 1965, as I watched a ship docking and the hustle and bustle accompanying it, a young European-looking male approached me from among the passengers. He introduced himself as John Taylor, American Peace Corps worker, residing further south in the province of Cotabato. He had decided to take the ship from Manila, disembark in Iligan and take the short plane trip to his destination in Cotabato. By this time, darkness had fallen.

He asked about the availability of overnight accommodation in a hotel or boarding house. I suggested he stay with us in the parish house as there were many empty rooms. He accepted my offer. Then he asked if Galway had won the All-Ireland football final the previous week. He was disappointed we had not heard the result and informed me that he was from my home county, Galway. After a meal at a local Chinese café, we returned to the parish house.

As he was leaving early the next morning for the airport and was tired from his boat trip, he retired to his room. The next morning, after coffee and toast, I took him to the airport. We talked about a whole variety of issues of interest. As we waited for his flight to be called, I asked him where in Galway he was from. He answered, Clonberne - my home parish in Galway! He informed me that he was adopted as a young baby by a family I knew of in the south end of the rural parish, reared and educated by them. After finishing high school, he decided to emigrate to the United States like many of his fellow Irish young men and women at that time. While settling and working in New York, he continued his education at night. Then he joined the Peace Corps and was assigned to Cotabato in the Philippines.

By the time we bade each other goodbye at the boarding gate, we were both tearful. Flabbergasted, I returned to my car and made my way back to the parish house.

Many times since, I have reflected on this incident and why I enjoyed going to the docks, watching ships and people come and go. Was it unconscious loneliness or homesickness on my part - a need to be connected to imaginary strangers, expecting someone I knew to arrive from home? Was I alone in feeling that way? Had I not yet built a home in my inner landscape to house my emotions of loss and change in my new surroundings? Were refugees, immigrants and displaced people who felt similar longings comforted by a mental tourist brochure of home?

Many years later, I read Lonely Londoners by Sam Selvon, which tells of Moses, a West Indian immigrant in London, going to meet a friend at Waterloo Station who had disembarked earlier from a ship at Southampton. On arrival at Waterloo, Moses rushes into the station and immediately has a feeling of homesickness like he’s never had before - it is because Waterloo is a station of arrival from the West Indies. Sam tells of West Indians in London going to Waterloo Station to meet boat trains containing passengers from the West Indies. They watch people arrive and sometimes spot somebody they know and find out what is happening back home - the latest calypso number perhaps, or who has recently died.

Reflecting on my visits to the docks in Iligan and having read Sam Selvon’s book, I have come to realise there are others like me experiencing departure, separation, homesickness and loneliness and that we all have unconscious ways of coping. Like Moses, I, too, had a soft feeling each time I went to the docks in Iligan. My journey had not really ended at Manila Airport.

Mystical hope is not tied to good outcomes, to the future. It lives a life of its own, seemingly without reference to external circumstances and conditions (Cynthia Bourgealt).

Columban Fr Bobby Gilmore lives and works in Ireland.