Pope Francis - Portrait: BogdanSolomenco (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Papa_Francesco_designed_by_Bogdan_Solomenco.jpg), https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/legalcode

Pope Francis - Portrait: BogdanSolomenco (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Papa_Francesco_designed_by_Bogdan_Solomenco.jpg), https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/legalcode

Pope Francis and St Francis on the “periphery” of inter-religious dialogue

When Archbishop David Moxon, director of the Anglican Centre in Rome, invited me to give a presentation at the Centre, he suggested the topic: “The Francis Effect: A Close Walk with Pope Francis and His Inspiration, Francis of Assisi”.

My own patron, St Columban, gives us the vision to be pilgrims for Christ, peregrinari pro Christo, and I suppose another translation of peregrinari is to “wander”. So, I hope you will forgive me if I have wandered too far from the charted path Archbishop David gave me and wilfully led elsewhere under the topic: “Pope Francis and St Francis and the ‘periphery’ of inter-religious dialogue”.

Since I came to Rome in 2011, the Anglican Centre in Rome has been where my heart is at home. Missionary activity without a commitment to and engagement in ecumenism is a dead duck.

It seems to me that considering “Pope Francis and St Francis and the ‘periphery’ of inter-religious dialogue” takes on special relevance in the immediately “now” context of the massive people movement taking place in Europe from both Africa (through Italy) and Syria and other Middle Eastern countries (especially through Greece and beyond). I am at the same time concerned that issues in inter-religious dialogue are being seen majorly in terms of Islam and Muslims with the result that the wellsprings of devotion and holiness manifested by Hindus, Buddhists, and Sikhs and other believers are being marginalised and even, can we say, peripheralized.

For example, an article in the June 2015 issue of the Australian Journal of Mission Studies savaged St Francis of Assisi. St Francis, as you may know, joined the boats carrying the 5th Crusade in 1219 and got himself to Damietta on a missionary journey to convert Sultan Malik al Kamil. Before this, in 2012, he had set off on a missionary journey to Syria but didn’t get very far as he was shipwrecked on the other side of the Adriatic.

Afterwards, in 1213, he tried to go to Morocco but became desperately ill while travelling south through Spain. We find this urge of the heart of St Francis towards Muslims manifested in the Rule that he wrote in 1223 at Fonte Colombo near Rieti with a sense of desperation to ensure his vision for his brothers when he appealed to them to go among Muslims in a peaceful way.

However, this article I have referred to claims that Francis compromised himself by travelling in the boats connected with the 5th Crusade: “His intentions were good but his association with the 5th Crusade conveyed a contrary message.” Leaving aside the fact that Ryanair wasn’t about at the time and that the only way to get to Egypt 800 hundred years ago was to get on one of the many boats sailing back and forward with the Crusaders, it is more helpful to see what Sultan Malik thought about Francis’s arrival at his court.

Francis was a dishevelled, unkempt man like the many dervishes and malangs that must have infested Malik’s court at Damietta. Orthodox Christians, in the pay of the Sultan, would have been there as well. So, Francis’s appearance was not that of a Christian coming to the court but “an odd man from the West” appearing suddenly on the Sultan’s doorstep. According to the Fioretti di San Francesco, the Sultan and his advisors prepared a trap for Francis, much like what happened in Iran after the fall of the Shah when crosses were painted on the floors at the entrances to public buildings so that people would walk on them in derision.

When Francis was invited to meet the Sultan (and he was invited, not dragged in as a prisoner), carpets were laid at the entrance with crosses woven into them. Francis strolled happily forward, looking towards the Sultan without worrying where his feet fell. Mocked for walking on the cross, his sacred sign, Francis is reported to have cheerily said: “We have the True Cross. You have the crosses of the two thieves, and that is what I am walking on.” I can imagine the applause that must have come at Francis’s quick-witted and sensible repartee. He may have thrown off the clothes of his father when he chose Lady Poverty, but he still had the sharp wit and capacity for happy banter in which he was educated by his mother.

We know nothing more except that the Sultan set Francis on his way, moved no doubt by his encounter with this strangely holy man. It seems to me that not only has the author of the article I have referred to mistaken history but has, more seriously, misread the hearts of both Francis and Sultan Malik.

St Francis of Assisi

St Francis of Assisi

Francis lived on the margins of society in Italy and struggled to remain on the ecclesiastical periphery where he would not be overwhelmed by the world of popes and cardinals and the demands on him to write a “sensible” Rule. He travelled to a far periphery in Syria to meet the Sultan. The periphery for Francis was not simply a geographic measurement to be travelled. He had what I want to call an “inner periphery”, which impelled him and enabled him to move imaginatively well beyond. I think St Paul was impelled by this “inner periphery” when he said Caritas Christi urget nos, “the love of Christ impels us” beyond the beyond.

I see Pope Francis summoning us to walk back both imaginatively and re-creatively where we have plodded in the past and, at the same time, to be impelled creatively and happily by our own personal inner periphery to live and move and have our being in the context of the religious, political, social, and economic peripheries of our world.

Our unlimited “inner periphery” enables us to stretch beyond, to imagine beyond, to think of the possibilities rather than the obstacles, from the perspective of ad maiorem Dei gloriam (For the greater glory of God) without a preoccupation with where I stand in the pecking order. I think it is a sort of “partially realised immortality”, as a movement into the limitlessness of God. Pope Francis encourages us to have a religious imagination that engages our inner periphery so that we may keep seeking God in all things.

For many people, the challenge and distant margin of fruitful inter-religious dialogue (some prefer to say interfaith dialogue) sit out there on the intellectual or faith periphery as unachievable. Often the reference point is that because there is so much religious-based terrorism, then we need to have religious dialogue to back the fires and cool the tensions and be seen to be doing something or other. Violence in the name of God has penetrated the streets of London, Paris, Melbourne, and Sydney, without speaking of the awful bestialities being committed in Syria, Nigeria, and Sahel Africa and elsewhere. The response to this is not a knee-jerk “let’s dialogue” or throwing money at committees to de-radicalise youth. As Pope Francis said in 2014 while in Jerusalem and Pope Benedict said in 2009 at Regensburg, there must be a rallying cry for solidarity between men and women of goodwill against the violence of fundamentalism, to name the evil, and to embrace one another in the heart: “May no one abuse the name of God through violence.” The issue, of course, at the heart of fundamentalist-based violence is not religion but atheism, which denies the divine reality of God and elevates a humanly constructed control model to which God is expected to conform.

This is why I am speaking about the periphery of religious dialogue with all believers and not just Muslims because they happen to be “in the news”. This sort of periphery is not an unachievable but an expanded religious imagination that enables our hearts to dialogue, a dialogue that is more primary than the activity of our minds. Sixty years ago, Nostra Aetate from Vatican II, the document on other faiths, called us to have the religious imagination to be able to recognize truth and holiness in other religions. This was part of the breakthrough language at Vatican II, and I feel it is a language still waiting to break through now 60 years later.

There is a wonderful Urdu proverb that seems to have been made to describe the dialogue of believers: dil se dil tak rah hoti hai - or the surest road is the one that runs from one heart to another. Cardinal Newman had a similar motto: cor ad cor loquitur - or heart speaks to heart. For St Francis, it didn’t matter what he was or wasn’t standing on when he came to meet the Sultan. I like to think that the only people during that encounter in Damietta in 1219 who knew what was going on were Francis and the Sultan through their encounter in the heart. The rest of them, with their games, just did not matter.

In his first message in January 2014 for the World Day of Peace, Fraternity, the Foundation and Pathway to Peace, Pope Francis spoke repeatedly about fraternity. It has been his constant message ever since.

Pope Francis has called us to communion in our hearts. He has appealed to us to build bridges. “Fraternity”, “communion”, “bridges”: I think that taking these from Pope Francis and joining them to the call of Nostra Aetate to recognise truth and holiness in the hearts of believers can nurture in us the religious imagination needed for dialogue. Pope Francis shows us that what enables us to use our religious imagination in dialogue is a commitment to compassion and a readiness to be pilgrims who are explorers who are not self-sufficient and who cannot afford to be superior.

Columban Fr Robert McCulloch is Rector of Collegio San Colombano in Rome.

Listen to "The 800th Anniversary of the Franciscans"

Related links

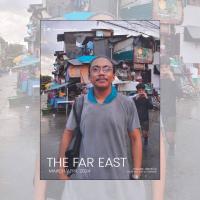

- Read more from The Far East - March/April 2024